Ireland Leads in Fight For Manufacturing Jobs For Now

These are good days for Ireland’s manufacturers as a resurgent economy driven by home-grown and foreign investment provide the biggest turnaround since the financial collapse 10 years ago, writes John Whelan.

Irish manufacturing firms recorded the highest increase in industrial production across all EU countries in the year to August 2018, according to new Eurostat figures.

The rate of growth at 15% was particularly striking — the average industrial growth rate recorded across all EU countries was a mere 1.2% in the period.

To put the performance in perspective, manufacturing now accounts for almost a third of all economic output by GDP, double of the share of a decade ago of 17%, and well above the global average, leaving countries such as Germany, the US, and the UK well behind.

The dramatic growth in Irish industrial production shows that Government policies to rescue the sector after decades of neglect and decline have borne fruit.

There has been a push by many governments across the world, and not just in President Donald Trump’s America, to pull their economies out of the recession by pushing for more manufacturing in their home bases.

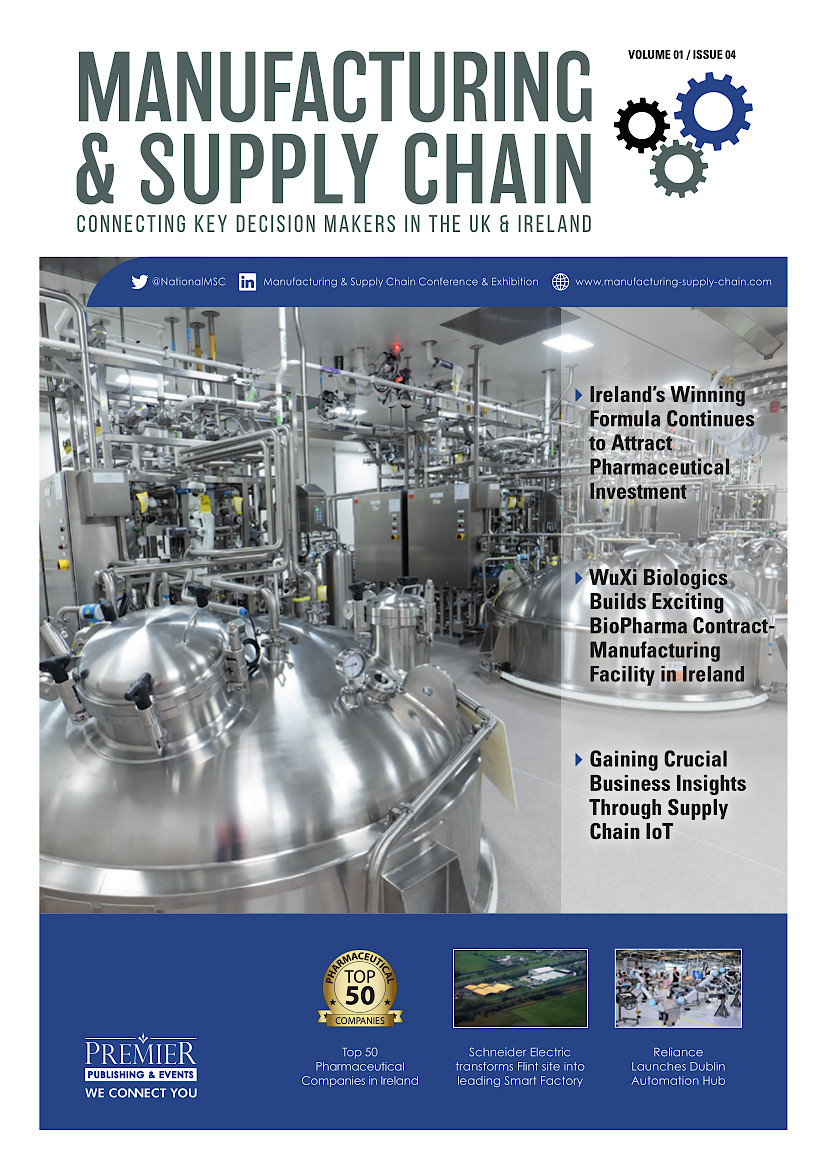

The results in Ireland have come about by incentivising foreign companies such as Intel, Medtronic, Schneider Electric, Cook medical Ireland, Boston Scientific, to name just a few.

But the indigenous sector has also moved significantly into the holy grail of advanced manufacturing and robotics with strong support from Enterprise Ireland.

“Making it in Ireland; Manufacturing 2020” was the policy document released in the thick of the recession in 2012 as the Fine Gael Government came to power and needed to get Ireland back to work quickly.

Abroad, Narendra Modi, the Indian prime minister, introduced his “Make in India” programme in 2016 achieving spectacular success attracting investments from firms such as General Motors, and from Korea’s oldest car manufacturer KIA.

In August, the Chinese government launched “Made in China 2025”, a state-led industrial policy that seeks to make China dominant in global manufacturing. The Chinese move, in particular, enraged President Trump who sees the move as one that may undermine his “Make America Great Again” mantra.

However, behind the bluster, US administrators know that manufacturing has become a very competitive game. Earlier this month, Washington released its “Strategy for American Leadership in Advanced Manufacturing”.

The US administration said at the time: “This century saw dramatic changes with significant decline in US manufacturing employment starting in the 1990s and accelerating losses during the 2008 recession.

“In the face of intense global competition, the Trump Administration has taken strong action to defend the economy… strong actions are required to combat unfair global trade practices and help US manufacturers reach their full potential.”

The UK has shown up as one of the laggards with industrial production growth of 1.6% in the year to August. It is finding difficulty moving up its production base from below 10% of national output where it has been stuck for the past decade.

Amid weaker international demand for British goods, its manufacturers have suffered negative growth in the first six months this year — meeting definitions for an economic recession in the sector.

They face a difficult autumn as the Brexit deadlock continues and Trump’s trade sanctions hit exports. England’s misfortune could be Ireland’s opportunity.

But the fight for manufacturing jobs has become a key focus of so many major economies that it may not be a case of jobs moving from Britain to Ireland, but from Europe to Asia, or to the US.

On the immediate horizon, there is the worrying move by the White House which last week notified US Congress of its intent to start three separate trade agreement talks with Japan, the EU, and the UK.

The US has a trade deficit with all three of these regions. That means the US will buy fewer products made in Ireland, the rest of the EU, as well as from the UK and Japan.

John Whelan is a leading consultant on Irish and international trade.